Practical Reverse Engineering Part 2 - Scouting the Firmware

29 Apr 2016- Part 1: Hunting for Debug Ports

- Part 2: Scouting the Firmware

- Part 3: Following the Data

- Part 4: Dumping the Flash

- Part 5: Digging Through the Firmware

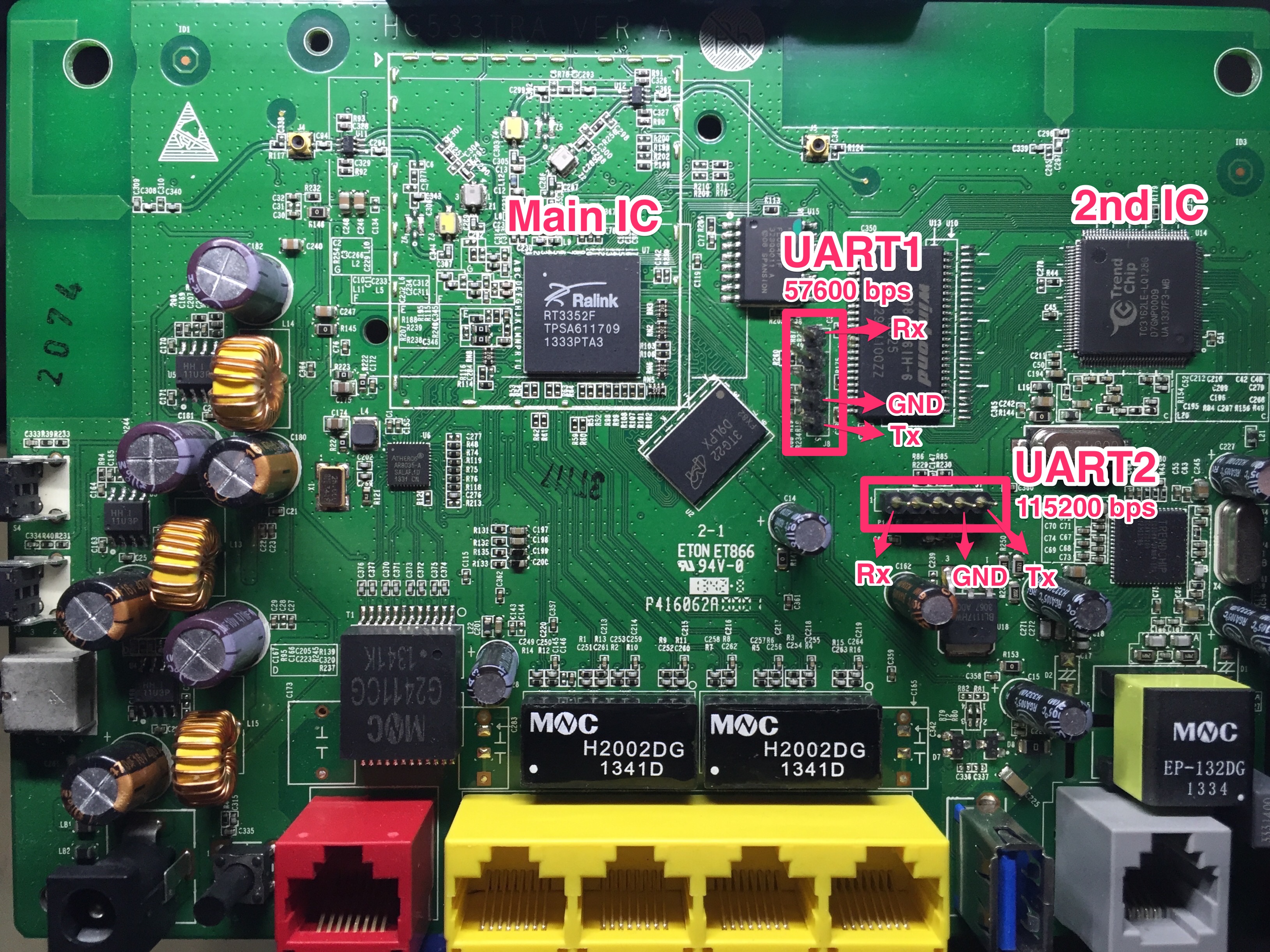

In part 1 we found a debug UART port that gave us access to a Linux shell. At this point we’ve got the same access to the router that a developer would use to debug issues, control the system, etc.

This first overview of the system is easy to access, doesn’t require expensive tools and will often yield very interesting results. If you want to do some hardware hacking but don’t have the time to get your hands too dirty, this is often the point where you stop digging into the hardware and start working on the higher level interfaces: network vulnerabilities, ISP configuration protocols, etc.

These posts are hardware-oriented, so we’re just gonna use this access to gather some random pieces of data. Anything that can help us understand the system or may come in handy later on.

Please check out the legal disclaimer in case I come across anything sensitive.

Full disclosure: I’m in contact with Huawei’s security team; they’ve had time to review the data I’m going to reveal in this post and confirm there’s nothing too sensitive for publication. I tried to contact TalkTalk, but their security staff is nowhere to be seen.

Picking Up Where We Left Off

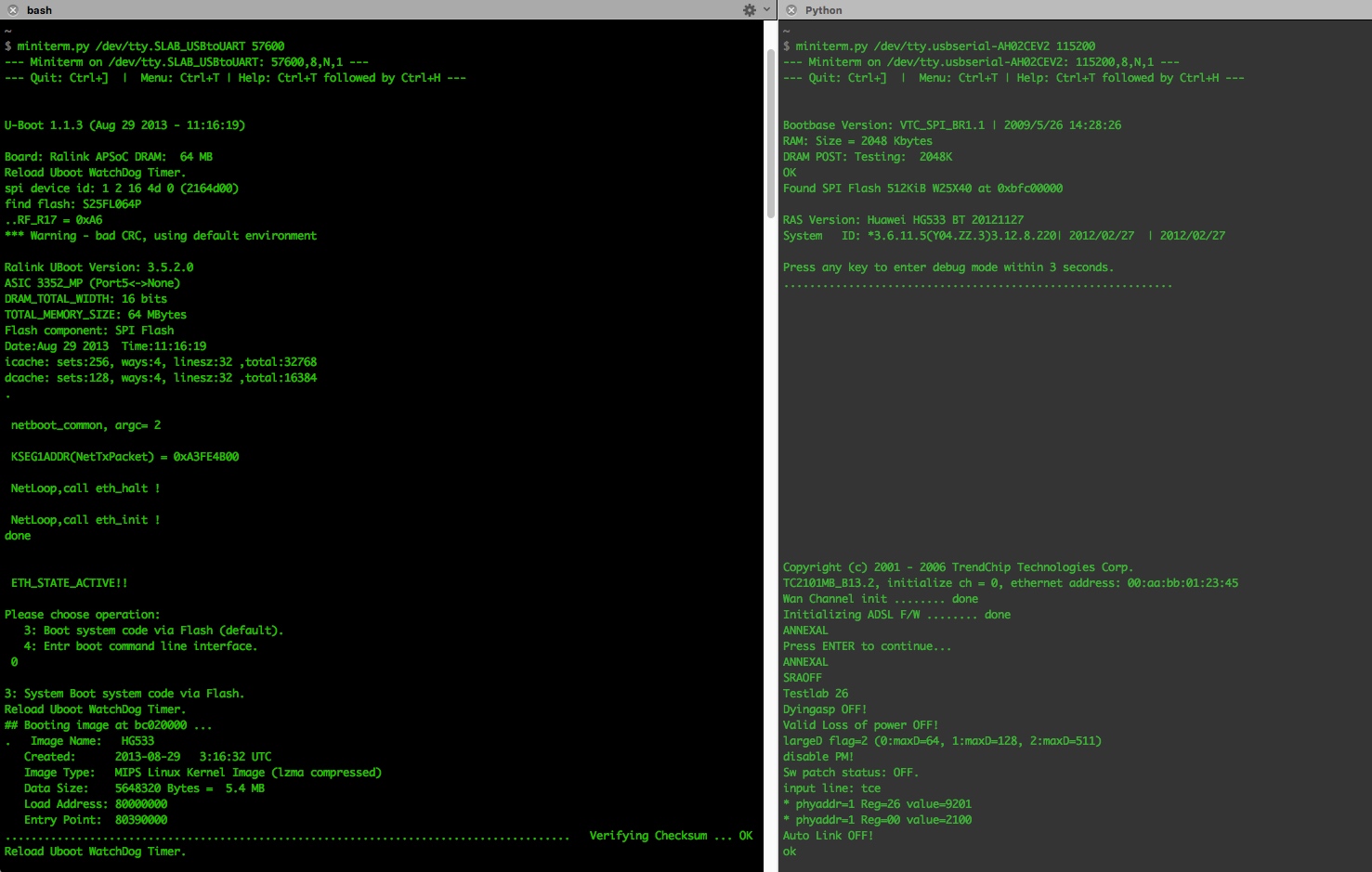

We get our serial terminal application up and running in the computer and power up the router.

We press enter and get the login prompt from ATP Cli; introduce the

credentials admin:admin and we’re in the ATP command line. Execute the command

shell and we get to the BusyBox CLI (more on BusyBox later).

-------------------------------

-----Welcome to ATP Cli------

-------------------------------

Login: admin

Password: #Password is ‘admin'

ATP>shell

BusyBox vv1.9.1 (2013-08-29 11:15:00 CST) built-in shell (ash)

Enter 'help' for a list of built-in commands.

# ls

var usr tmp sbin proc mnt lib init etc dev bin

At this point we’ve seen the 3 basic layers of firmware in the Ralink IC:

- U-boot: The device’s bootloader. It understands the device’s memory map, kickstarts the main firmware execution and takes care of some other low level tasks

- Linux: The router is running Linux to keep overall control of the hardware, coordinate parallel processes, etc. Both ATP CLI and BusyBox run on top of it

- Busybox: A small binary including reduced versions of multiple linux

commands. It also supplies the

shellwe call those commands from.

Lower level interfaces are less intuitive, may not have access to all the data and increase the chances of bricking the device; it’s always a good idea to start from BusyBox and walk your way down.

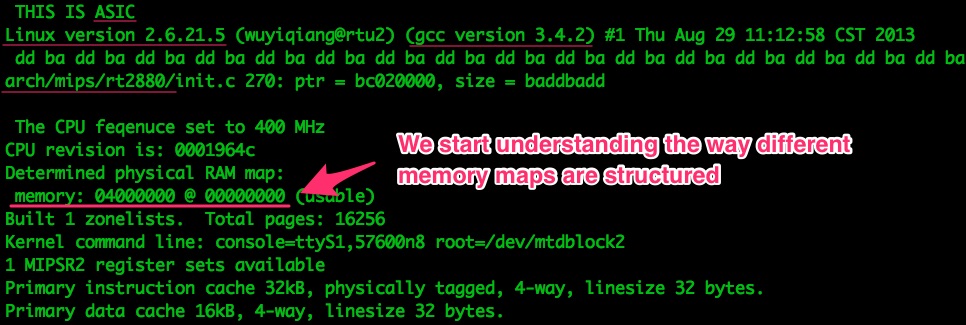

For now, let’s focus on the boot sequence itself. The developers thought it would be useful to display certain pieces of data during boot, so let’s see if there’s anything we can use.

Boot Debug Messages

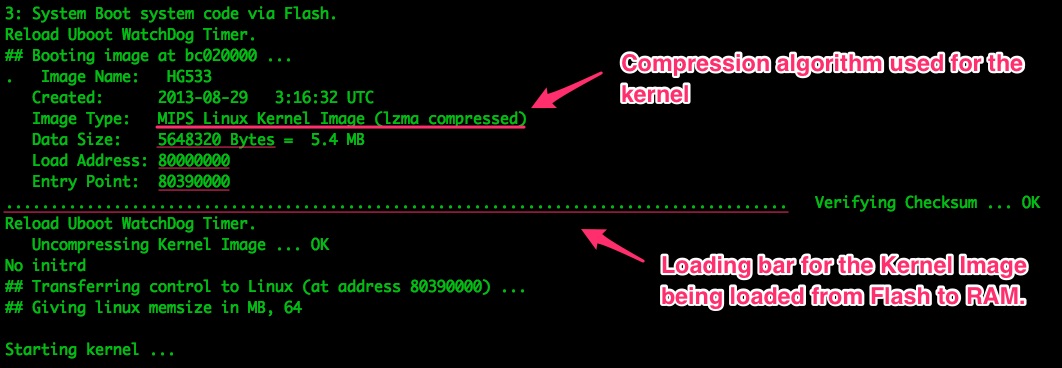

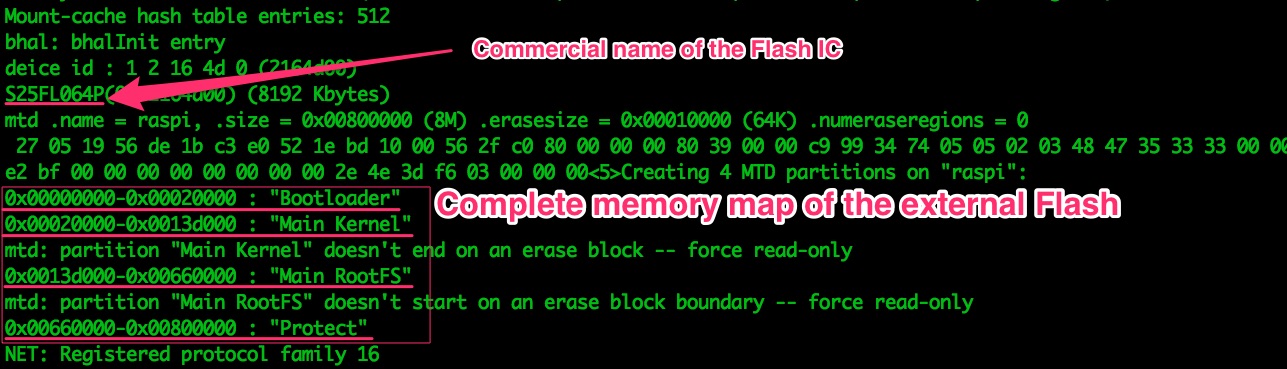

We find multiple random pieces of data scattered across the boot sequence. We’ll find useful info such as the compression algorithm used for some flash segments:

Intel on how the external flash memory is structured will be very useful when we get to extracting it.

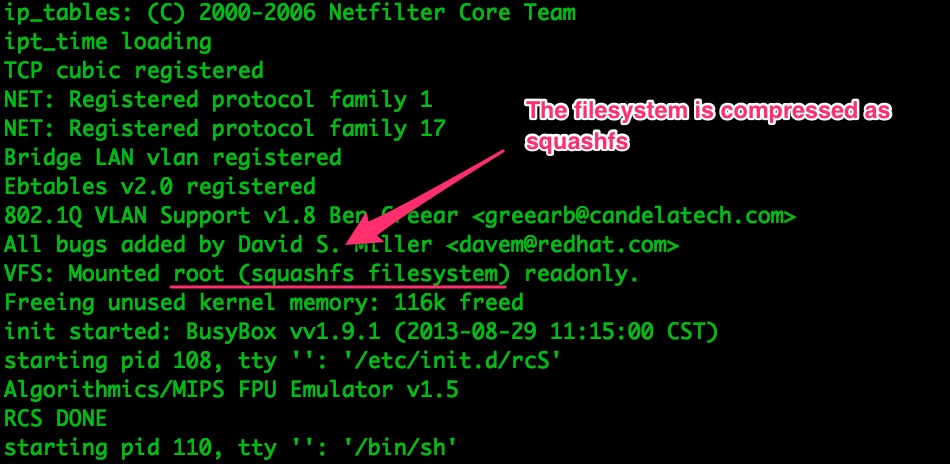

And more compression intel:

We’ll have to deal with the compression algorithms when we try to access the raw data from the external Flash, so it’s good to know which ones are being used.

What Are ATP CLI and BusyBox Exactly? [Theory]

The Ralink IC in this router runs a Linux kernel to control memory and parallel

processes, keep overall control of the system, etc. In this case, according to

the Ralink’s

product brief,

they used the Linux 2.6.21 SDK. ATP CLI is a CLI running either on top of

Linux or as part of the kernel. It provides a first layer of authentication into

the system, but other than that it’s very limited:

ATP>help

Welcome to ATP command line tool.

If any question, please input "?" at the end of command.

ATP>?

cls

debug

help

save

?

exit

ATP>

help doesn’t mention the shell command, but it’s usually either shell or

sh. This ATP CLI includes less than 10 commands, and doesn’t support any kind

of complex process control or file navigation. That’s where BusyBox comes in.

BusyBox is a single binary containing reduced versions of common unix

commands, both for development convenience and -most importantly- to save memory.

From ls and cd to top, System V init scripts and pipes, it allows us to

use the Ralink IC somewhat like your regular Linux box.

One of the utilities the BusyBox binary includes is the shell itself, which has access to the rest of the commands:

ATP>shell

BusyBox vv1.9.1 (2013-08-29 11:15:00 CST) built-in shell (ash)

Enter 'help' for a list of built-in commands.

# ls

var usr tmp sbin proc mnt lib init etc dev bin

#

# ls /bin

zebra swapdev printserver ln ebtables cat

wpsd startbsp pppc klog dns busybox

wlancmd sntp ping kill dms brctl

web smbpasswd ntfs-3g iwpriv dhcps atserver

usbserver smbd nmbd iwconfig dhcpc atmcmd

usbmount sleep netstat iptables ddnsc atcmd

upnp siproxd mount ipp date at

upg sh mldproxy ipcheck cwmp ash

umount scanner mknod ip cp adslcmd

tr111 rm mkdir igmpproxy console acl

tr064 ripd mii_mgr hw_nat cms ac

telnetd reg mic ethcmd cli

tc radvdump ls equipcmd chown

switch ps log echo chmod

#

You’ll notice different BusyBox quirks while exploring the filesystem, such

as the symlinks to a busybox binary in

/bin/.

That’s good to know, since any commands that may contain sensitive data will

not be part of the BusyBox binary.

Exploring the File System

Now that we’re in the system and know which commands are available, let’s see if there’s anything useful in there. We just want a first overview of the system, so I’m not gonna bother exposing every tiny piece of data.

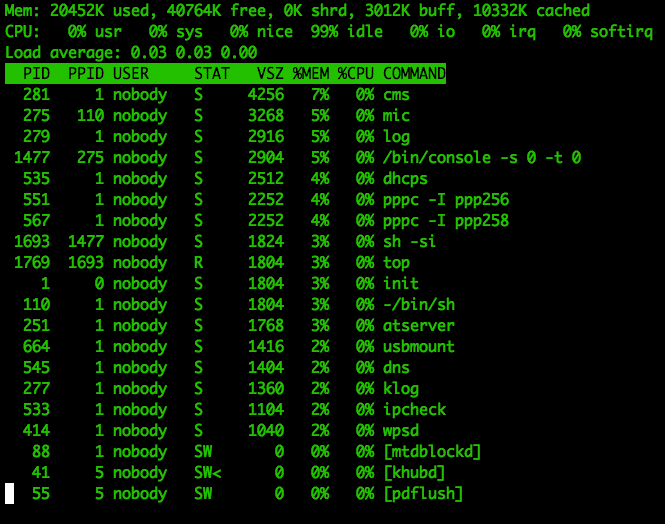

The top command will help us identify which processes are consuming the most

resources. This can be an extremely good indicator of whether some processes are

important or not. It doesn’t say much while the router’s idle, though:

One of the processes running is usbmount, so the router must support connecting

‘something’ to the USB port. Let’s plug in a flash drive in there…

usb 1-1: new high speed USB device using rt3xxx-ehci and address 2

[...]

++++++sambacms.c 2374 renice=renice -n +10 -p 1423

The USB is recognised and mounted to /mnt/usb1_1/, and a samba server is

started. These files show up in /etc/samba/:

# ls -l /etc/samba/

-rw-r--r-- 1 0 0 103 smbpasswd

-rw-r--r-- 1 0 0 0 smbusers

-rw-r--r-- 1 0 0 480 smb.conf

-rw------- 1 0 0 8192 secrets.tdb

# cat /etc/samba/smbpasswd

nobody:0:XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX:564E923F5AF30J373F7C8_______4D2A:[U ]:LCT-1ED36884:

More data, in case it ever comes in handy:

- netstat -a: Network ports the device is listening at

- iptables –list: We could set up telnet and continue over the network, but I’d rather stay as close to the bare metal as possible

- wlancmd help: Utility to control the WiFi radio, plenty of options available

- /etc/profile

- /etc/inetd

- /etc/services

- /var/: Contains files used by the system during the course of its operation

- /etc/: System configuration files, etc.

/var/ and /etc/ always contain tons of useful data, and some of it makes

itself obvious at first sight. Does that say /etc/serverkey.pem??

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

It’s common to find private keys in embedded systems. They could be RSA private keys used for mutually-authenticated TLS connections with a server, variables buried in a file to be loaded by an application, etc. By accessing 1 single device via hardware you may obtain the keys that will help you eavesdrop encrypted connections, attack servers, end users or other devices in the fleet.

This key could be used to communicate with some server from Huawei or the ISP, although that’s less common. On the other hand, it’s also very common to find public certs used to communicate with remote servers.

In this case we find 2 certificates next to the private key; both are self-signed by the same ‘person’:

/etc/servercert.pem: Most likely the certificate for theserverkey- /etc/root.pem: Probably used to connect to a server from the ISP or Huawei. Not sure.

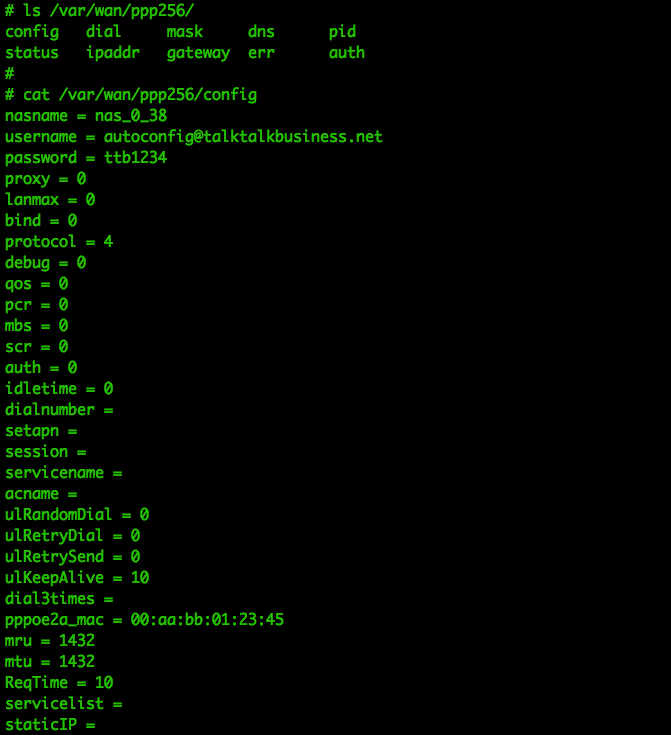

And some more data in /etc/ppp256/config and /etc/ppp258/config:

These credentials are also available via the HTTP interface, which is why I’m publishing them, but that’s not the case in many other routers (more on this later).

With so many different files everywhere it can be quite time consuming to go through all the info without the right tools. We’re gonna copy as much data as we can into the USB drive and go through it on our computer.

The Rambo Approach to Intel Gathering

Once we have as many files as possible in our computer we can check some things

very quick. find . -name *.pem reveals there aren’t any other TLS certificates.

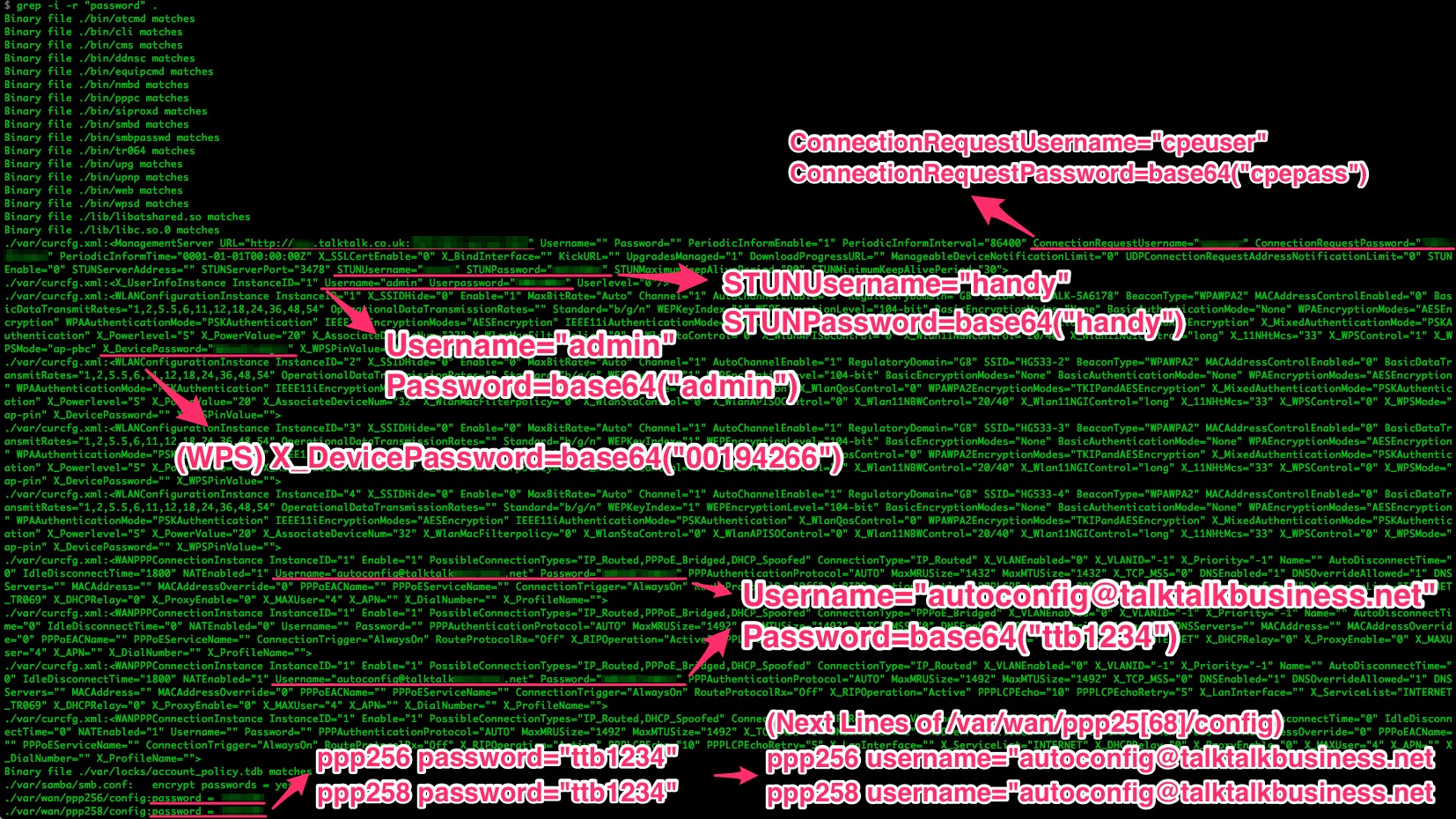

What about searching the word password in all files? grep -i -r password .

We can see lots of credentials; most of them are for STUN, TR-069 and local services. I’m publishing them because this router proudly displays them all via the HTTP interface, but those are usually hidden.

If you wanna know what happens when someone starts pulling from that thread, check out Alexander Graf’s talk “Beyond Your Cable Modem”, from CCC 2015. There are many other talks about attacking TR-069 from DefCon, BlackHat, etc. etc.

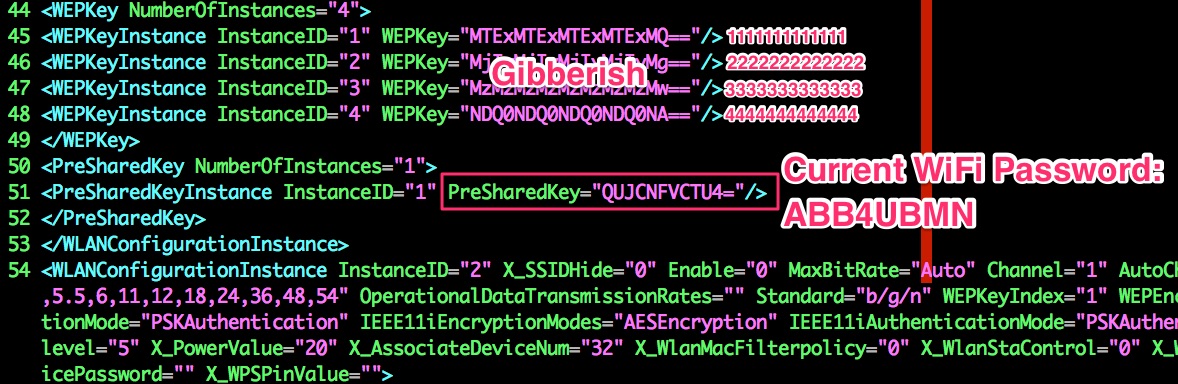

The credentials we can see are either in plain text or encoded in base64. Of course, encoding is worthless for data protection:

$ echo "QUJCNFVCTU4=" | base64 -D

ABB4UBMN

That is the current WiFi password set in the router. It leads us to 2 VERY interesting files. Not just because of their content, but because they’re a vital part of how the router operates:

- /var/curcfg.xml: Current configuration file. Among other things, it contains the current WiFi password encoded in base64

- /etc/defaultcfg.xml: Default configuration file, used for ‘factory reset’. Does not include the default WiFi password (more on this in the next posts)

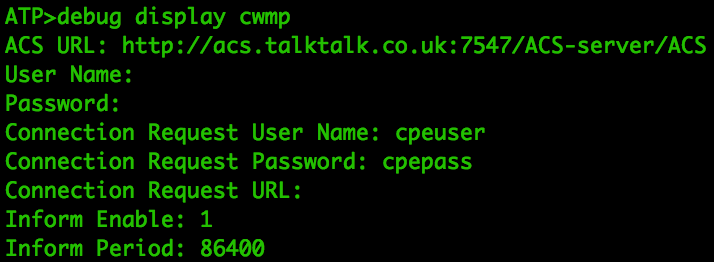

Exploring ATP’s CLI

The ATP CLI includes very few commands. The most interesting one -besides

shell- is

debug.

This isn’t your regular debugger; debug display will simply give you some info

about the commands igmpproxy, cwmp, sysuptime or atpversion.

Most of them

don’t have anything juicy, but what about cwmp? Wasn’t that related to remote

configuration of routers?

Once again, these are the CWMP (TR-069) credentials used for remote router configuration. Not even encoded this time.

The rest of the ATP commands are pretty useless: clear screen, help menu, save to flash and exit. Nothing worth going into.

Exploring Uboot’s CLI

The bootloader’s command line interface offers raw access to some memory areas. Unfortunately, it doesn’t give us direct access to the Flash IC, but let’s check it out anyway.

Please choose operation:

3: Boot system code via Flash (default).

4: Entr boot command line interface.

You choosed 4

Stopped Uboot WatchDog Timer.

4: System Enter Boot Command Line Interface.

U-Boot 1.1.3 (Aug 29 2013 - 11:16:19)

RT3352 # help

? - alias for 'help'

bootm - boot application image from memory

cp - memory copy

erase - erase SPI FLASH memory

go - start application at address 'addr'

help - print online help

md - memory display

mdio - Ralink PHY register R/W command !!

mm - memory modify (auto-incrementing)

mw - memory write (fill)

nm - memory modify (constant address)

printenv- print environment variables

reset - Perform RESET of the CPU

rf - read/write rf register

saveenv - save environment variables to persistent storage

setenv - set environment variables

uip - uip command

version - print monitor version

RT3352 #

Don’t touch commands like erase, mm, mw or nm unless you know exactly

what you’re doing; you’d probably just force a router reboot, but in some cases

you may brick the device. In this case, md (memory display) and printenv

are the commands that call my atention.

RT3352 # printenv

bootcmd=tftp

bootdelay=2

baudrate=57600

ethaddr="00:AA:BB:CC:DD:10"

ipaddr=192.168.1.1

serverip=192.168.1.2

ramargs=setenv bootargs root=/dev/ram rw

addip=setenv bootargs $(bootargs) ip=$(ipaddr):$(serverip):$(gatewayip):$(netmask):$(hostname):$(netdev):off

addmisc=setenv bootargs $(bootargs) console=ttyS0,$(baudrate) ethaddr=$(ethaddr) panic=1

flash_self=run ramargs addip addmisc;bootm $(kernel_addr) $(ramdisk_addr)

kernel_addr=BFC40000

u-boot=u-boot.bin

load=tftp 8A100000 $(u-boot)

u_b=protect off 1:0-1;era 1:0-1;cp.b 8A100000 BC400000 $(filesize)

loadfs=tftp 8A100000 root.cramfs

u_fs=era bc540000 bc83ffff;cp.b 8A100000 BC540000 $(filesize)

test_tftp=tftp 8A100000 root.cramfs;run test_tftp

stdin=serial

stdout=serial

stderr=serial

ethact=Eth0 (10/100-M)

Environment size: 765/4092 bytes

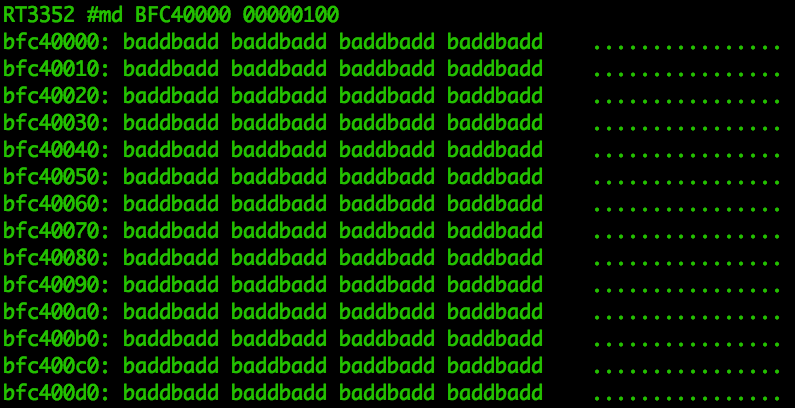

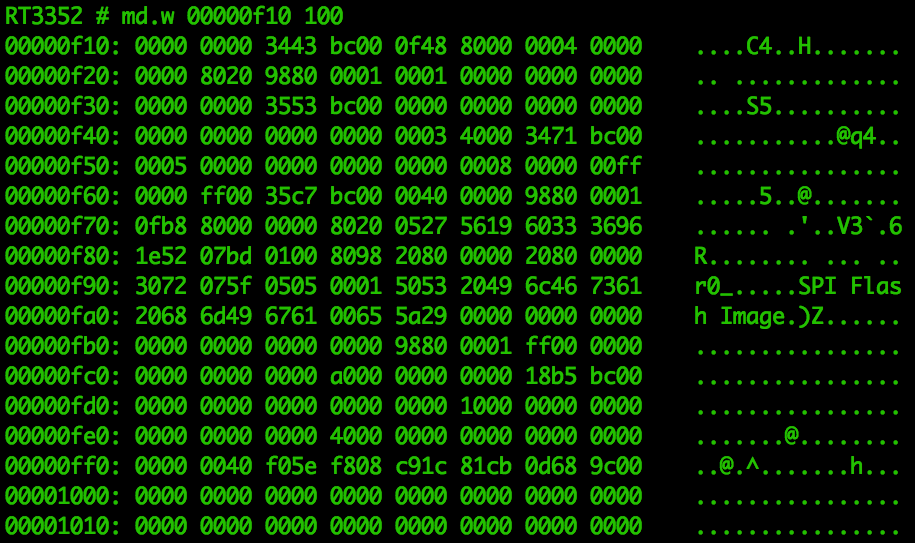

We can see settings like the UART baudrate, as well as some interesting memory

locations. Those memory addresses are not for the Flash IC, though. The flash

memory is only addressed by 3 bytes: [0x00000000, 0x00FFFFFF].

Let’s take a look at some of them anyway, just to see the kind of access this

interface offers.What about kernel_addr=BFC40000?

Nope, that badd message means bad address, and it has been hardcoded in md

to let you know that you’re trying to access invalid memory locations. These

are good addresses, but they’re not accessible to u-boot at this point.

It’s worth noting that by starting Uboot’s CLI we have stopped the router from loading the linux Kernel onto memory, so this interface gives access to a very limited subset of data.

We can find random pieces of data around memory using this method (such as that

SPI Flash Image string), but it’s pretty hopeless for finding anything specific.

You can use it to get familiarised with the memory architecture, but that’s about

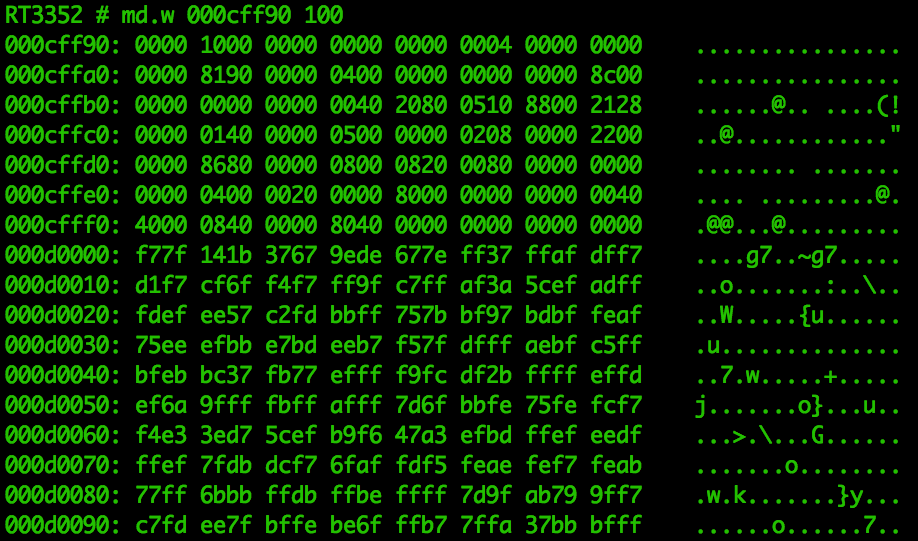

it. For example, there’s a very obvious change in memory contents at

0x000d0000:

And just because it’s about as close as it gets to seeing the girl in the red

dress, here is the md command in action. You’ll notice it’s very easy to spot

that change in memory contents at 0x000d0000.

Next Steps

In the next post we combine firmware and bare metal, explain how data flows and is stored around the device, and start trying to manipulate the system to leak pieces of data we’re interested in.

Thanks for reading! :)