Practical Introduction to BLE GATT Reverse Engineering: Hacking the Domyos EL500

19 Mar 2023My goal for this project was quite specific, leaving many details unexplored (for now). This post aims to be a quick reference for my future self, and to hopefully help anyone else who might be interested in doing something similar.

No security is bypassed, no exciting exploits are used, and no dangerous backdoors are found. We will simply connect to the device and determine how it works using straightforward methodologies.

Some decisions were made for the sake of my own learning, and might be simplified by using different tools and approaches. Consider following this guide if you are more interested in learning about BLE GATT than in discovering the fastest and most efficient tools.

The Target: Domyos EL500

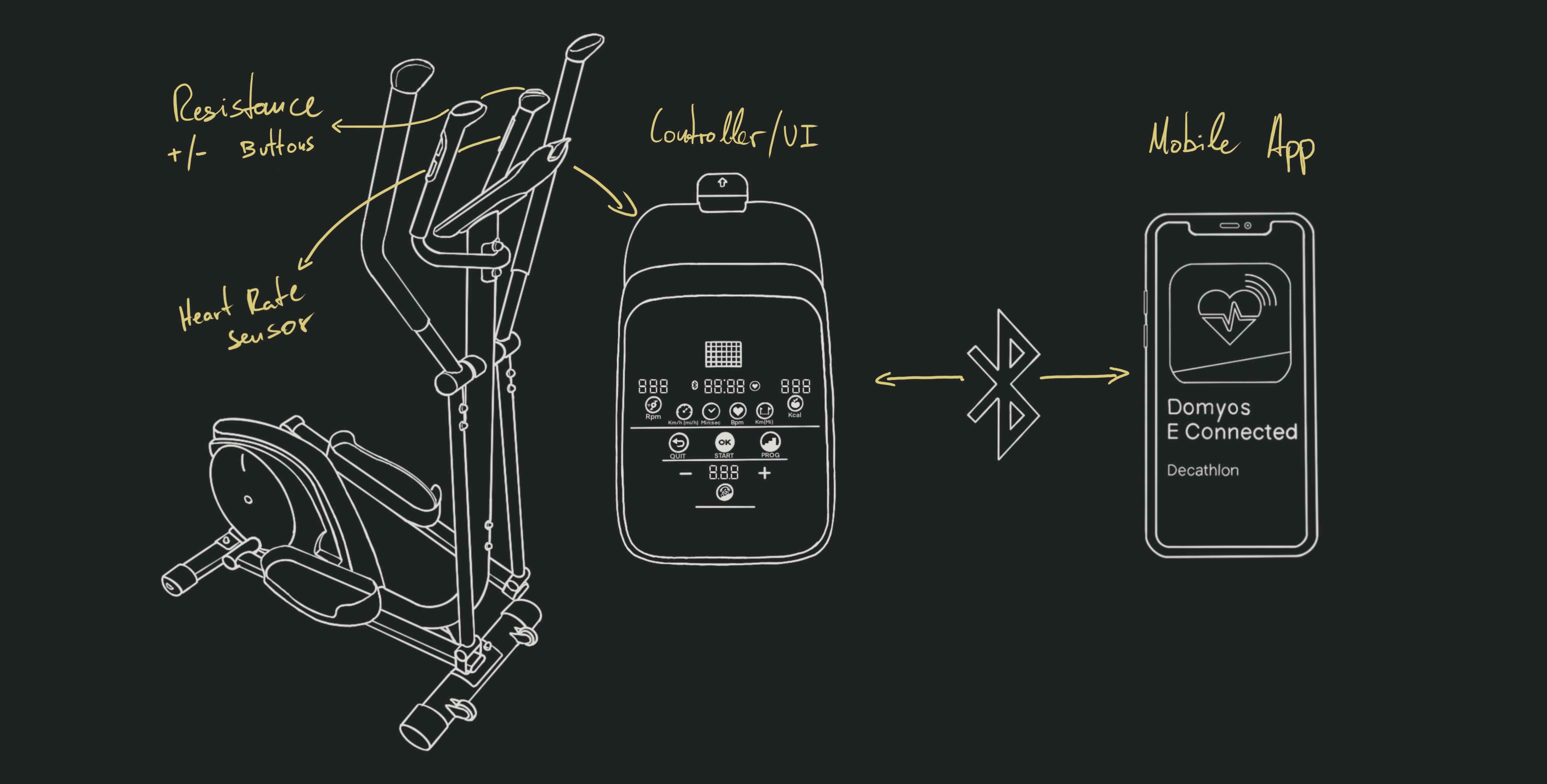

The EL500, is a cheap(ish) Bluetooth-enabled elliptical trainer sold by Decathlon. There’s no need to delve into too much detail; it’s an affordable machine with multiple resistance settings, a heart rate monitor, and Bluetooth connectivity.

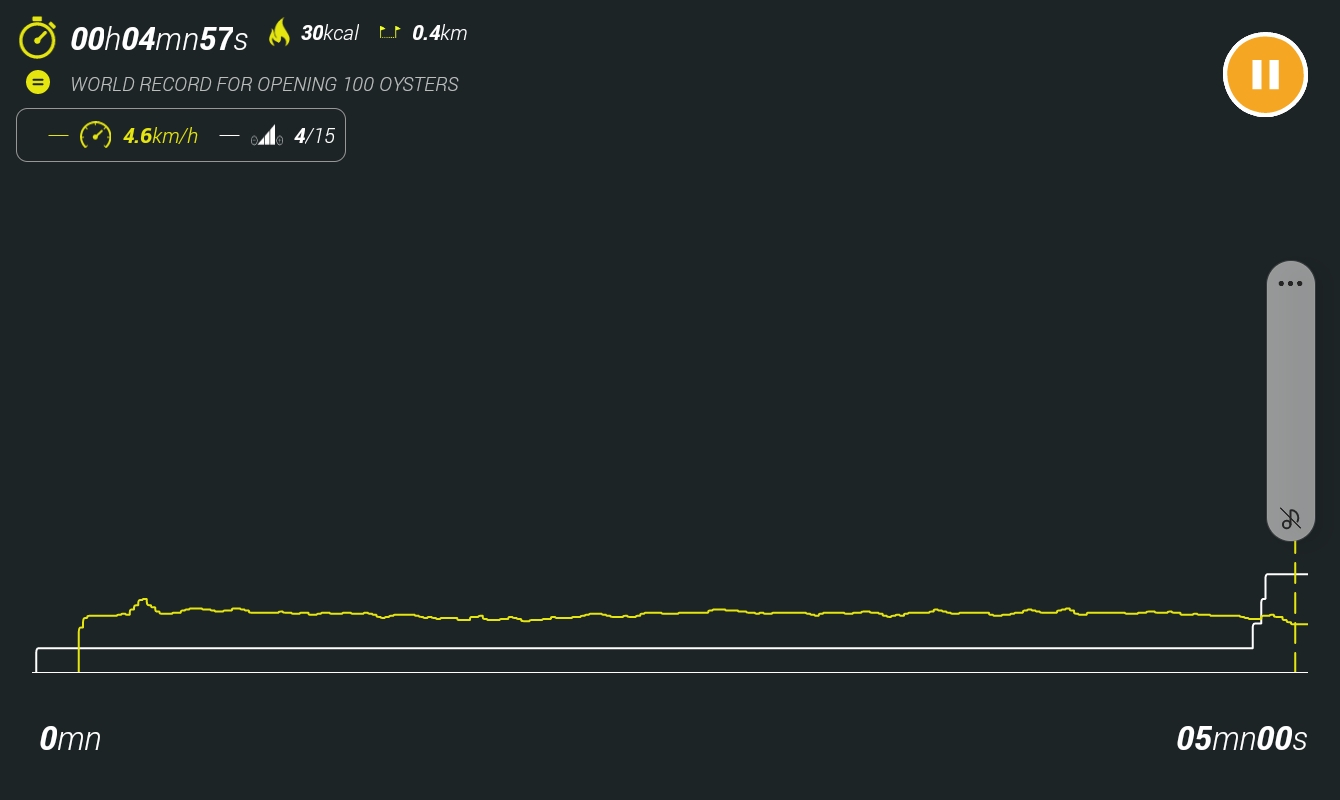

A mobile app called eConnected is provided to monitor the exercise session from your

smartphone, and save it for future reference as an image of a graph. The active

sessions look like this, and are saved as an image of that same graph:

I was interested in building a very specific user interface, and logging the data in much more detail, so I decided to reverse engineer the BLE comms, and build my own interface in Python. As one does…

First, we need to understand the basics of BLE, and the tools we’ll be using.

The Protocol: BLE GATT

BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) is a wireless communication technology for short-range comms between devices. BLE supports multiple profiles with different degrees of flexibility, data throughput, energy usage, etc.

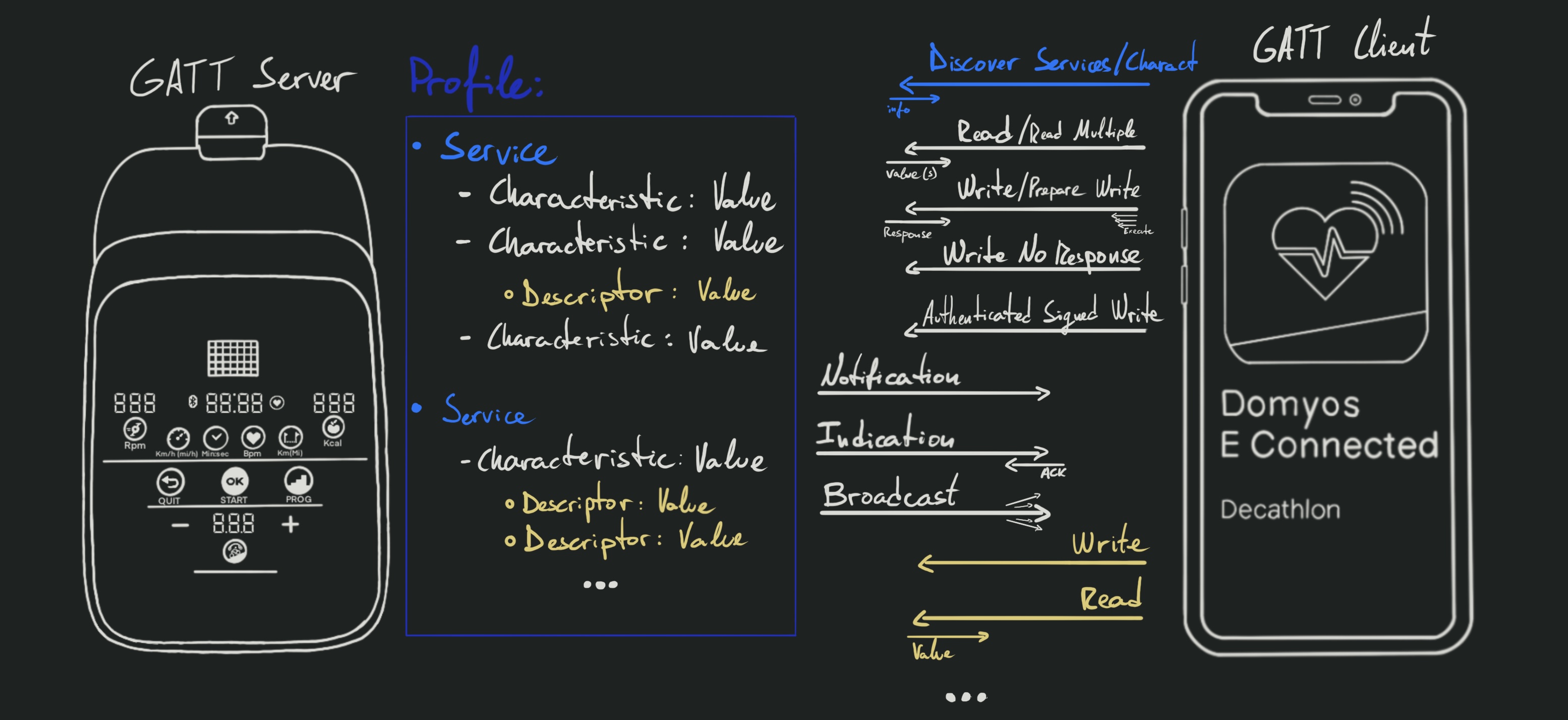

The BLE protocol we are interested in is GATT (Generic Attribute Profile); it is -AFAIK- the most commonly used on wireless devices to exchange arbitrary data. It is highly specified to facilitate interoperability, which plays to our advantage in the reverse engineering process.

Grossly oversimplifying things, a profile is a predefined collection of services, and each service contains a group of characteristics. Characteristics can have associated descriptors that provide metadata or connection-specific config options for their characteristic.

Here’s a diagram to illustrate the very basics:

We can easily start the device, discover it using some bluetooth tool, confirm that it is indeed running GATT, connect to it, and discover how the GATT properties are set up.

Even though this device -as so many others- does not seem to use any of the security mechanisms supported by BLE, they are still worth mentioning:

- Pairing:

The client and server go through a “secure” connection process to

authenticate each other and share the keys used for further communication.

The pairing process supports 4 different association models, each with its own

set of security properties and suitable differently abled devices:

- Just Works: Unauthenticated pairing process, common in devices without a screen or other means of presenting a pairing code. Since BLE 4.2’s “Secure Connections” (an upgrade to the older Secure Simple Pairing), the key exchange is performed with P-256 Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH), which protects the process against passive eavesdropping, but not so much against Man-in-the-Middle attacks.

- Numeric Comparison: The devices go through the ECDH key exchange, then share a secret and use it along with their respective private keys to compute the same pairing code. Each device displays the code to the user, who must confirm that the codes match on both devices.

- Passkey: One device displays a pairing code for the user to enter on the other device. Or, less commonly, the user enters the same code on both devices. The pairing code is used along the ECDH-derived shared secret to compute the encryption keys.

- Out of Band: The devices may or may not use ECDH to exchange keys, but they will use communication channels outside bluetooth to share some secure element(s). e.g. Tap the devices to kickstart an NFC-based key exchange, or have the device display a QR code for the user to scan from a mobile app, etc.

- Bonding: Akin to a website’s “remember me”. The paired devices exchange and store the necessary information to reconnect in the future without having to go through the pairing process again.

- Message Signatures: BLE devices can generate and use a dedicated signing key (CSRK) to digitally sign messages for authentication, integrity and non-repudiation purposes

- Authorization: The BLE spec accounts for the possibility of allowing different levels of access for connected clients. Given the nature of the feature, GATT can simply report if a given attribute requires authorization, but the product implications of that are left to the application layer

For more/better info, you should check out the BLE specifications published by the Bluetooth SIG. Or at least one of the countless BLE intros available online.

The Tools: bluetoothctl, nRF Connect, Android, BlueZ, gattacker…

Given the popularity of BLE in modern devices, there are plenty of tools to work with it. Some are for developers, others for users, or security researchers…

I’d classify them in 3 categories:

- Offensive tools: Made specifically to run attacks or offensive recon against BLE targets

gattacker,ubertooth, etc.

- System tools: Made to integrate and manage BLE on an OS

- Linux:

bluetoothctl,hcitool,bluez,gatttool, etc.

- Linux:

- Developer tools: Made to help developers create and debug their systems

- Android apps:

nRF Connect - Android:

Bluetooth HCI snoop logdeveloper mode option - BLE/GATT libraries:

bluepy,pygatt,gatt, embedded SDKs, Arduino libs, etc.

- Android apps:

I tried sniffing the traffic using ubertooth, if just to make sure there

was no funny business going on. But it is not worth the effort for a project like this.

Other than that, I decided against using any of the many offensive tools out there. I couldn’t be bothered to find a dongle that would support MAC vendor spoofing, worked well with my setup, etc.

Since this shouldn’t be a high effort target, I would rather build my own tools as necessary, and learn more along the way. YMMV.

The Process:

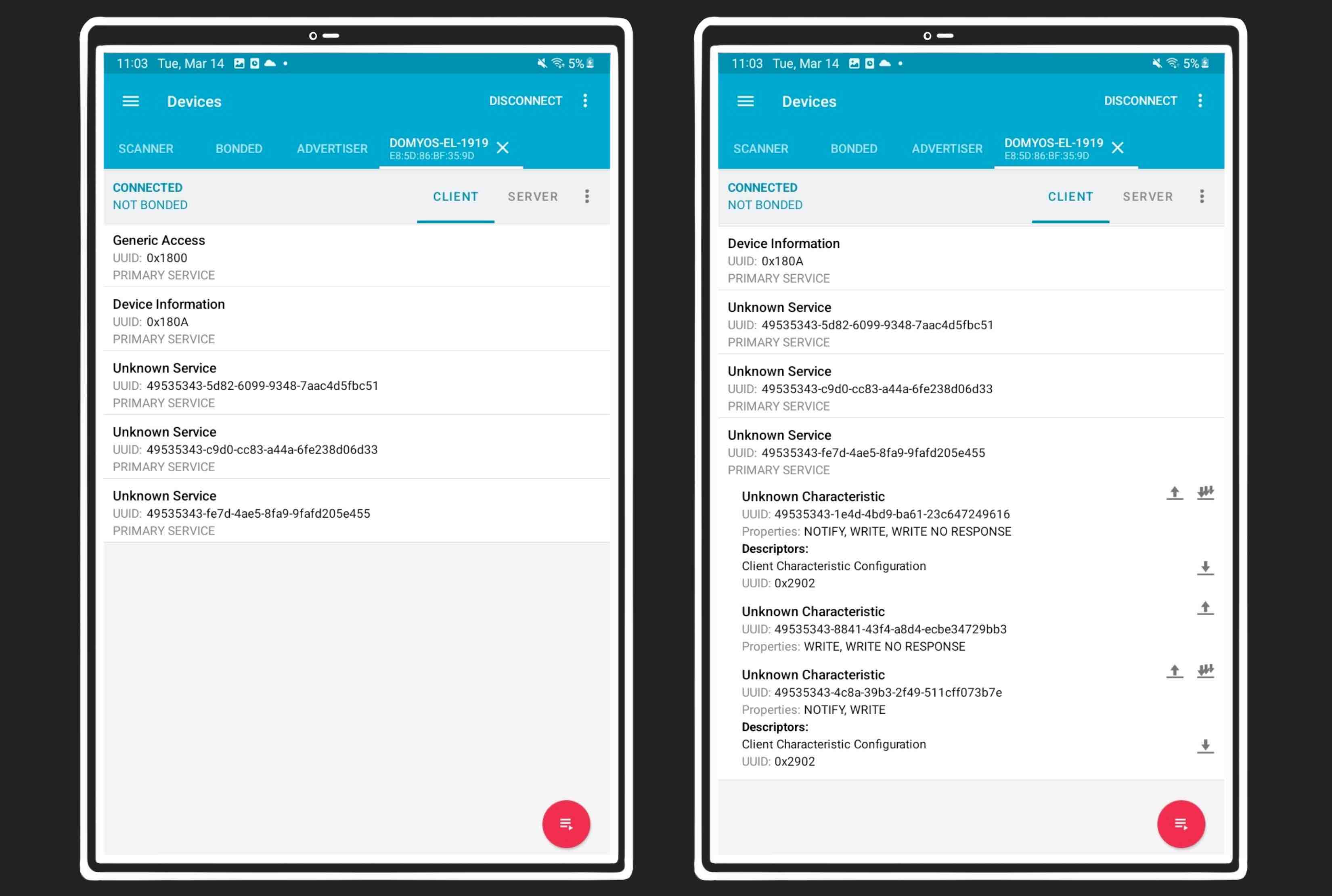

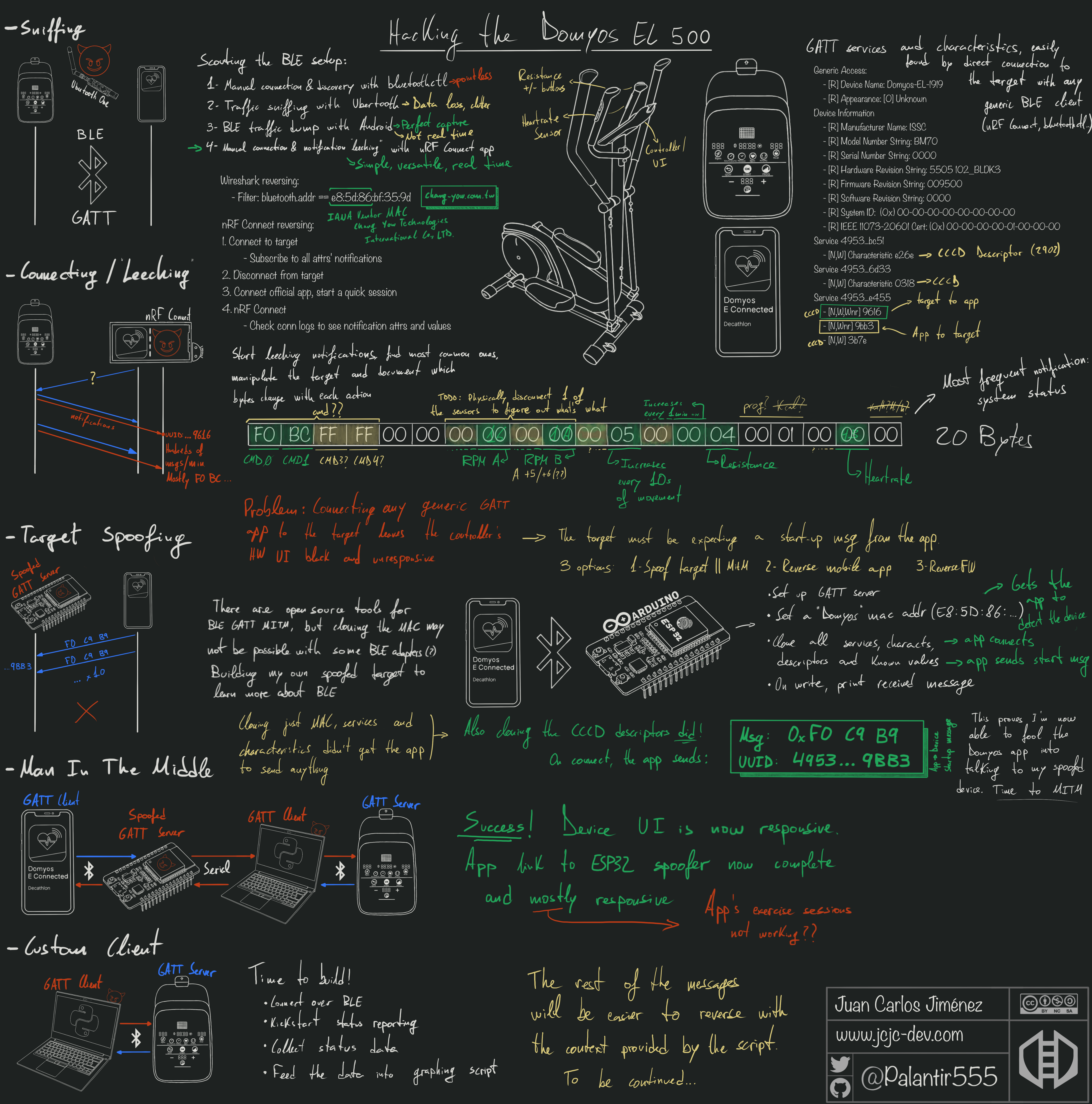

1. Scouting the GATT setup - Direct connection/discovery

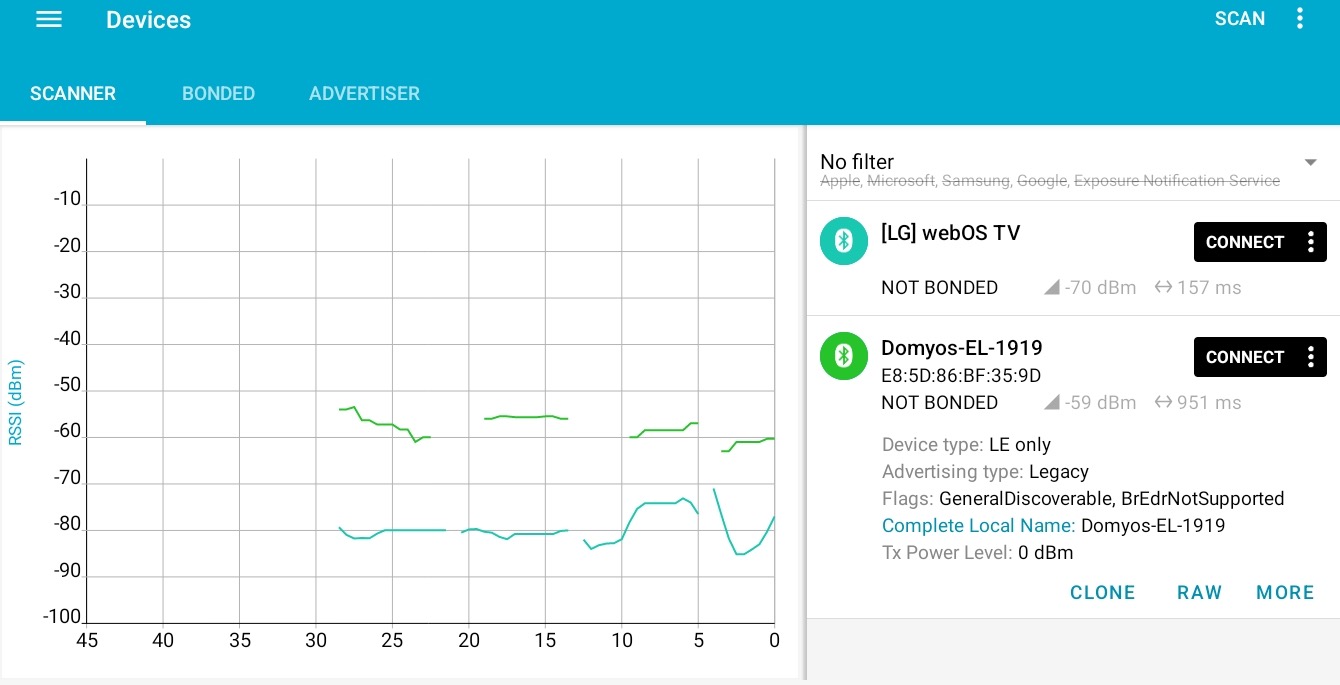

On Linux, bluetoothctl provides a straightforward way to quickly examine the

device. However, for speed and convenience, I recommend using the nRF Connect

app for Android. It’s simple, versatile, and has an intuitive UI. It’s also free

and doesn’t require complex setup or dedicated hardware.

Start the target EL500, use nRF Connect to discover it, connect to it,

and explore the services, characteristics and descriptors. Export the list and

save it:

This information can be enough for very simple devices. I’ve found devices that only had a couple of characteristics, and writing to them was enough to understand their purpose.

In this case, there’s a lot of characteristics. Enabling notifications in all of them from nRF connect is not enough to start receiving data, and writing random values to them also does nothing.

We need to understand what a regular conversation between the target and the official app looks like…

You could try using nRF Connect to spoof the target, and try to connect to it from the app on another phone. But if you need to spoof the MAC address to be recognized by the app -as is the case here- you’ll need to use a different approach…

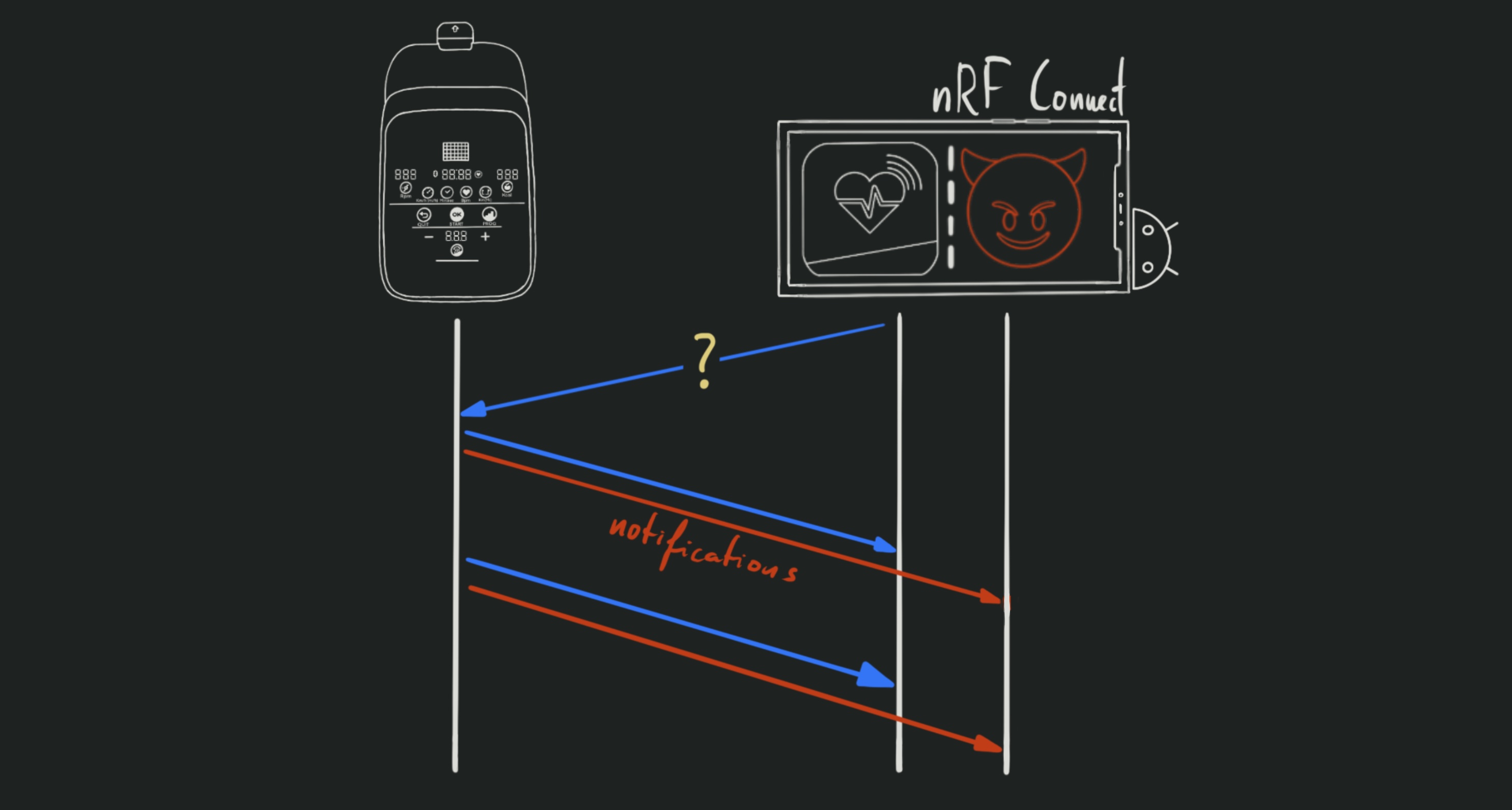

2. “Leeching” notifications

There’s probably a better term for this process (eavesdropping? piggybacking? not quite), but I personally refer to it as “leeching”:

- Connect to the device using

nRF Connect- Enable notifications for all characteristics that allow it - this will be remembered for the next connection

- Disconnect from the device

- Start the

eConnectedapp- Connect to the device - This should get

nRF Connectto auto-reconnect - Start a session

- Manipulate the device (walk, change resistance, measure heart rate, etc.)

- Connect to the device - This should get

- Observe the notifications received by

nRF Connect(should have auto-reconnected)

I like this process because it’s simple, extremely insightful, and perfectly within the BLE spec itself.

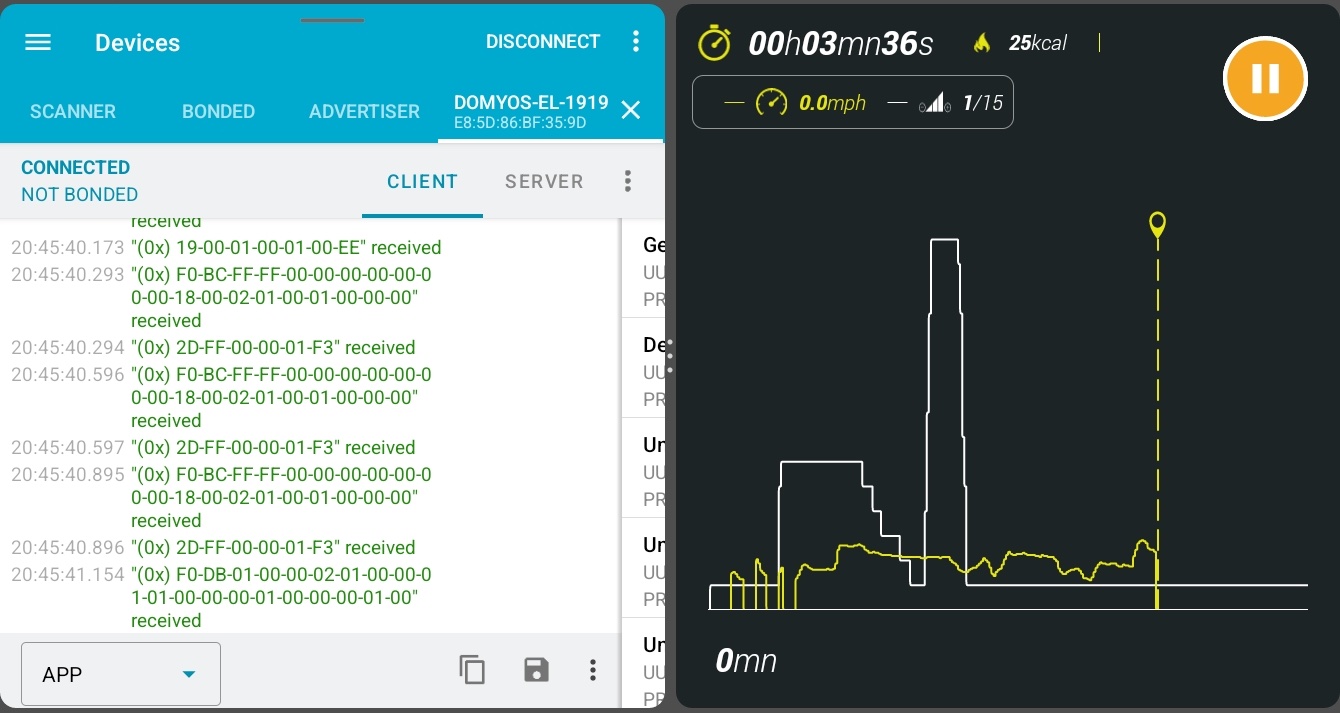

In this case, as soon as eConnected connects to the device, we start getting

flooded with notifications. They are sent to different characteristics, but some

useful patterns begin to emerge:

- Most notifications come from one characteristic:

49535343-1e4d-4bd9-ba61-23c647249616- This characteristic is likely used for most device to app communication, including status reports

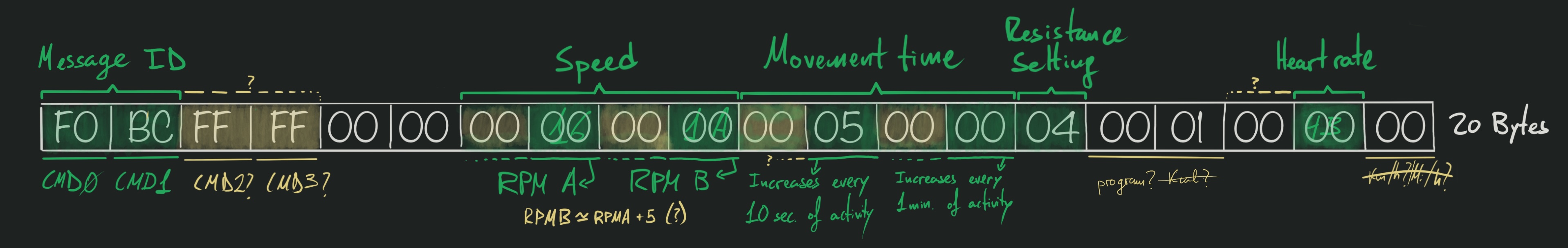

- About half the notifications are 20 bytes long, and start with the same 4 bytes:

F0-BC-FF-FF- If we group the notifications by length, plenty of those groups seem to have a common 2 to 4 bytes prefix, which would indicate the implementation uses a sort of message/command id for the notifications

We repeat the process multiple times, manipulating the device in different ways,

and exporting the logs from nRF Connect each time. Then we move them to a PC

for further analysis. Following this process, we can confirm that F0-BC messages

are reporting the device’s status, and we can start figuring out what each byte

in the message means:

I was hoping to find out what message is sent by the app in order to kickstart

the connection: I checked the logs for any messages with the same message ID that

was only sent once per session. I found one, but creating a clean session from

nRF Connect and sending that message to the same characteristic did not get the

device to do anything.

If the startup message is only passed through to the device’s logic, without notifying it to all subscribers (as would be expected), we’re gonna have to find it some other way.

Since the traffic does not seem to be encrypted, we could use android’s developer tools to dump the traffic and analyze it. I did it, but it’s rather slow and cumbersome, the data is hard to contextualize, etc.

Another quick way would probably be to reverse engineer the eConnected app and

figure out the entire protocol from there. Trying to dump the firmware, or find

and decrypt a firmware update file, would also be a valid attack vector, although

it would take a lot more effort and risk.

However, for this project, I’d prefer to continue with the wireless approach…

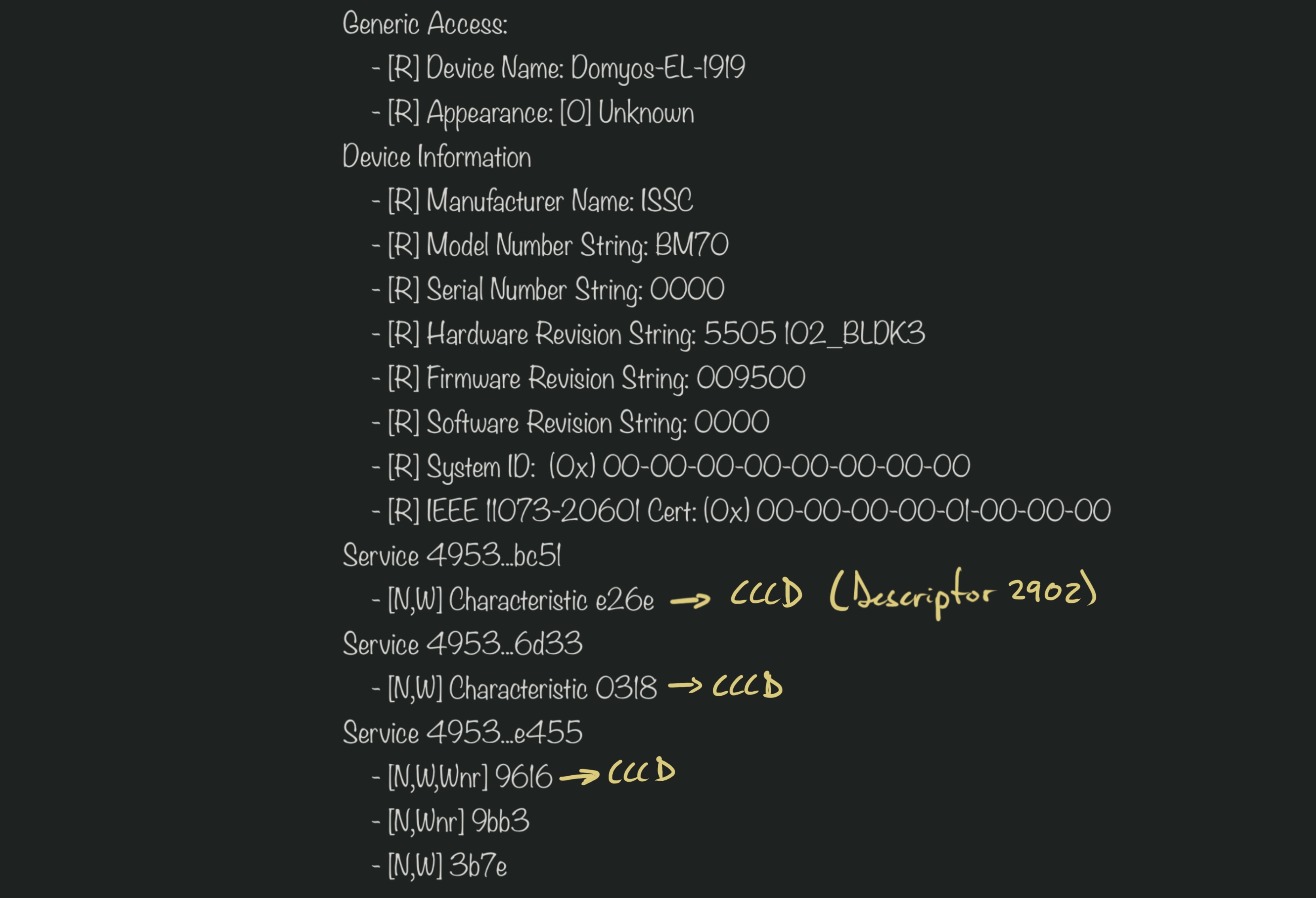

3. Target spoofing

If we can just fool the app into thinking our system is a legitimate device, it should send us the startup message…

With countless BLE devices advertising themselves everywhere, how can the app tell which BLE devices are Domyos eliptical trainers? A couple possible ways:

- Device MAC Address - The first 3 bytes are the vendor’s MAC address assigned by IANA

- Advertised data: Manufacturer data, services, etc.

Device Name(customizable by the user)

We have access to all this information in our target, so we can attempt to spoof it. My BLE adapter didn’t allow me to set a custom MAC address, and I couldn’t be bothered to search for one that does (I’ve done enough of that with Wi-Fi adapters over the years…).

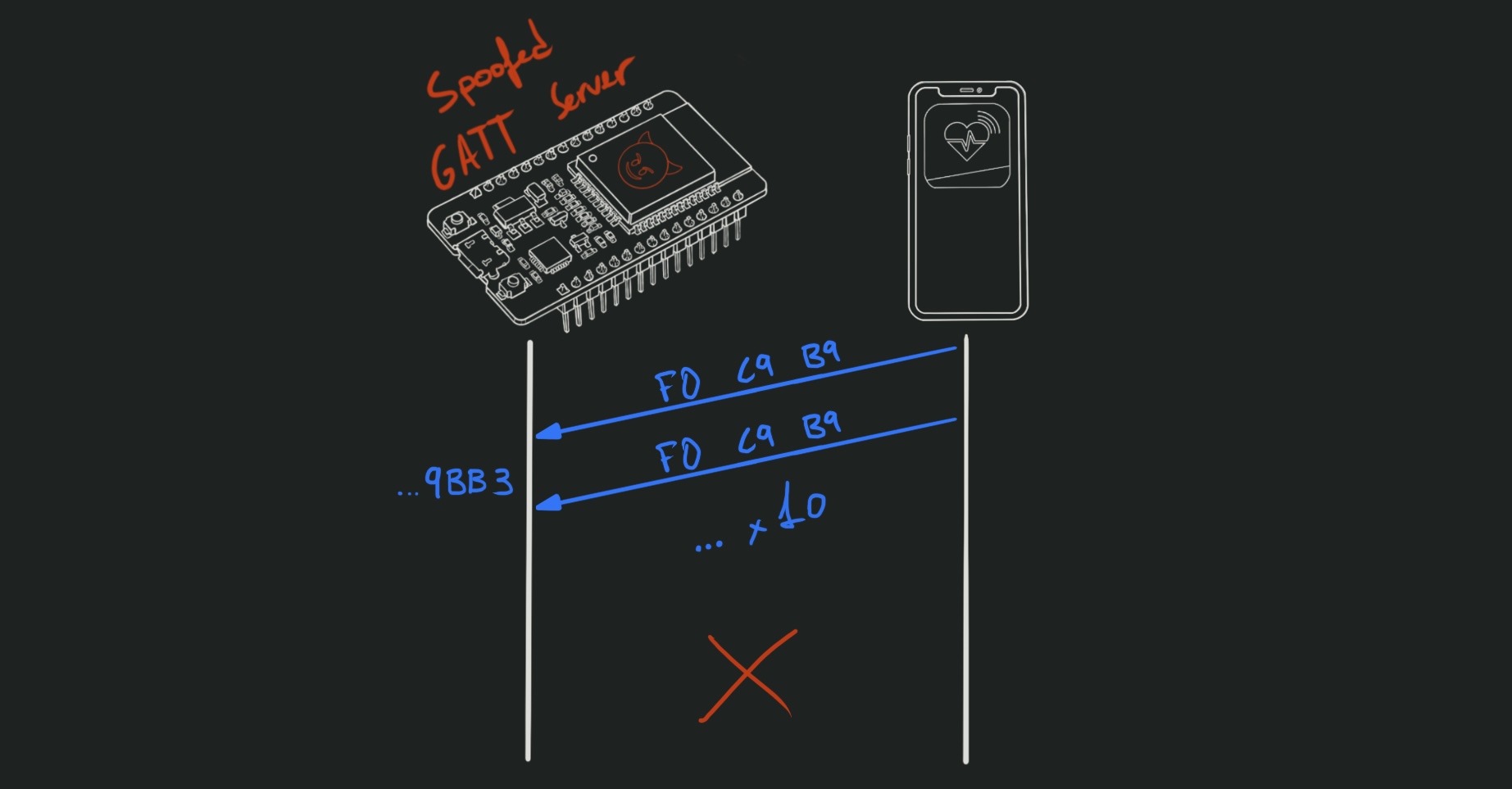

Instead, I decided to write a quick-n-dirty Arduino sketch for an ESP32 dev board. The modules running on these dev boards are designed to be integrated into real products, so it must have everything I need.

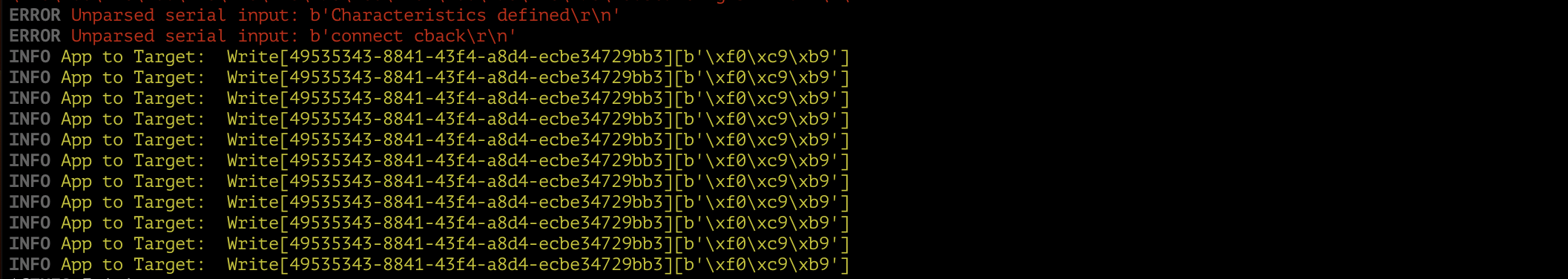

Cloning the vendor’s MAC address, services and characteristics was obvious enough. It got the app to display the spoofed device in the list of available devices. But it would not succeed when connect to it.

I also had to recreate the CCCDs (Client Characteristic Configuration Descriptors). Once I did, the app was able to connect to the device and start sending messages. It wrote the same message 10 times, then disconnected:

Using the iOS version of the eConnected app, the behavior was significantly

different, to the point of feeling buggy:

So, the app must now be expecting a message from the device before continuing the

converstaion… I could write it to the device using nRF Connect, then return

to the ESP for the subsequent message… But that’s gonna get annoying very quickly.

I’d rather automate the process.

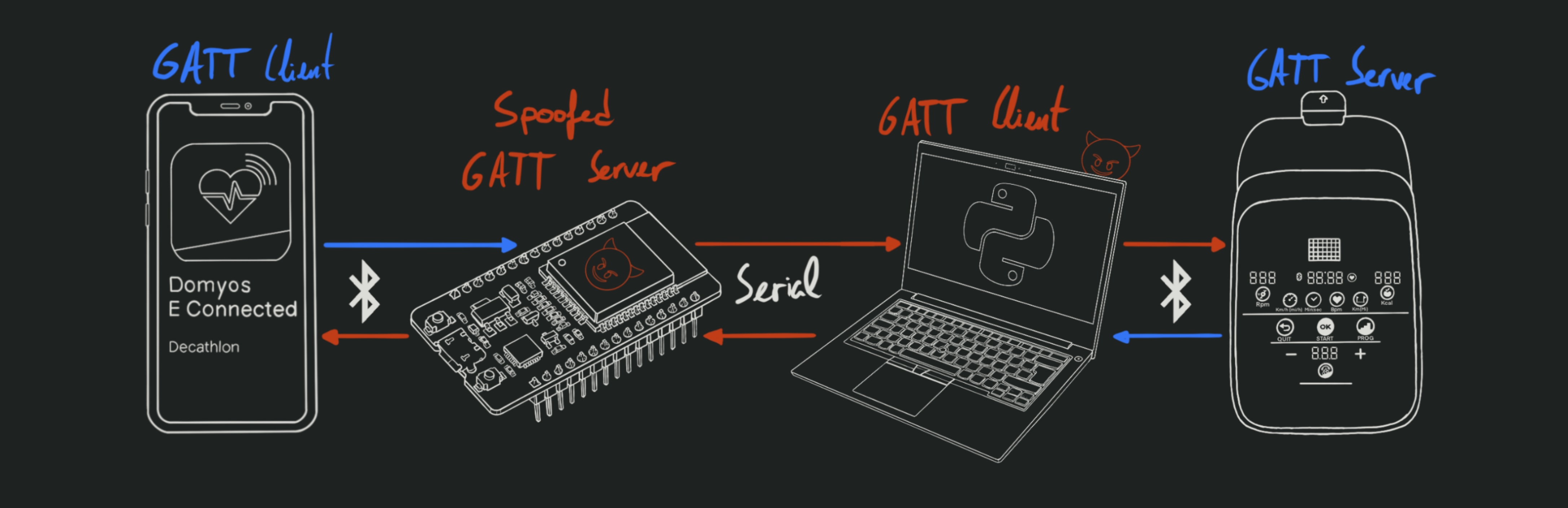

4. Man In The Middle

This would be time for any sensible person to find the right BLE dongle and offensive tool and get a standard MITM running in a few minutes. But where’s the fun in that?

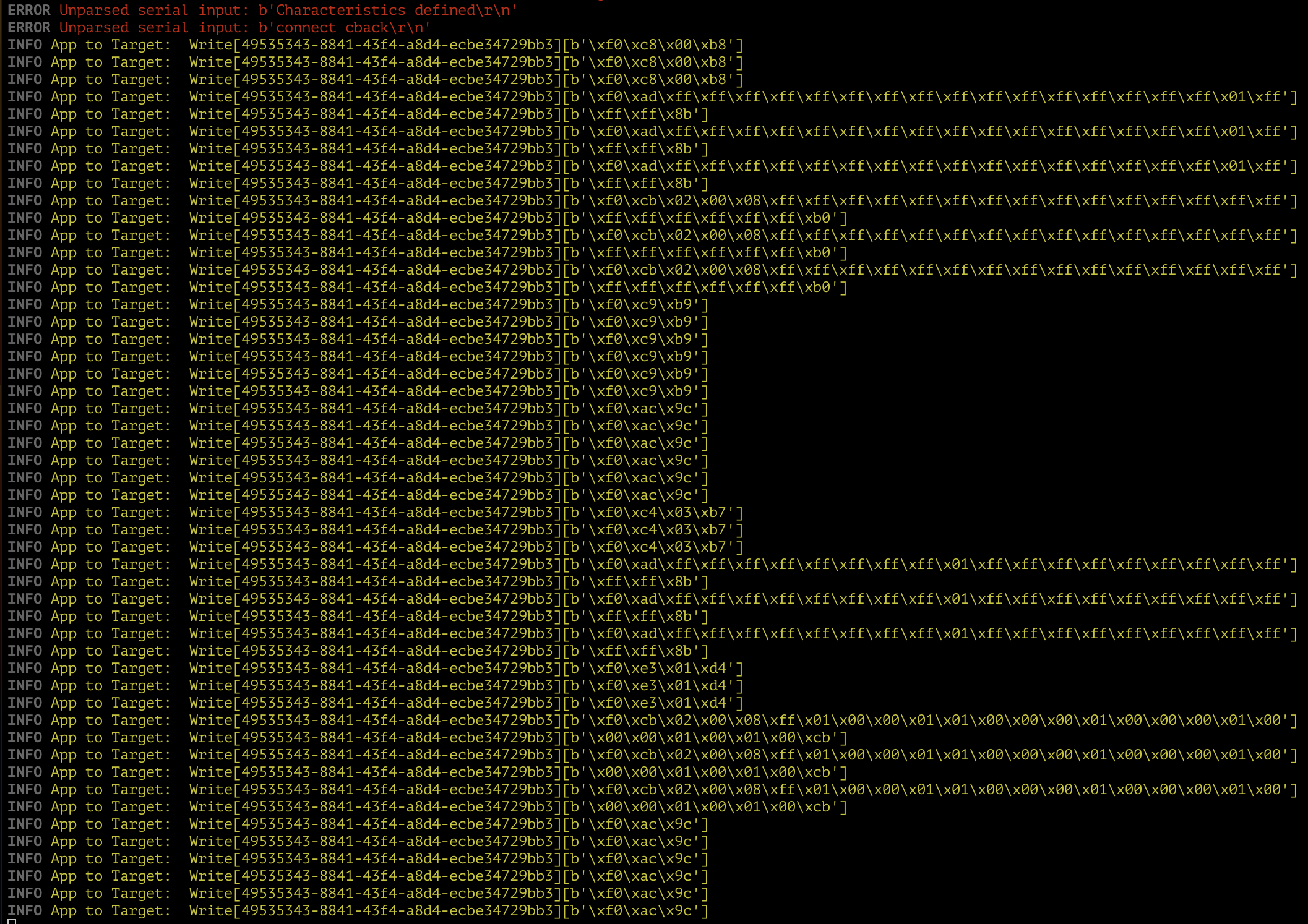

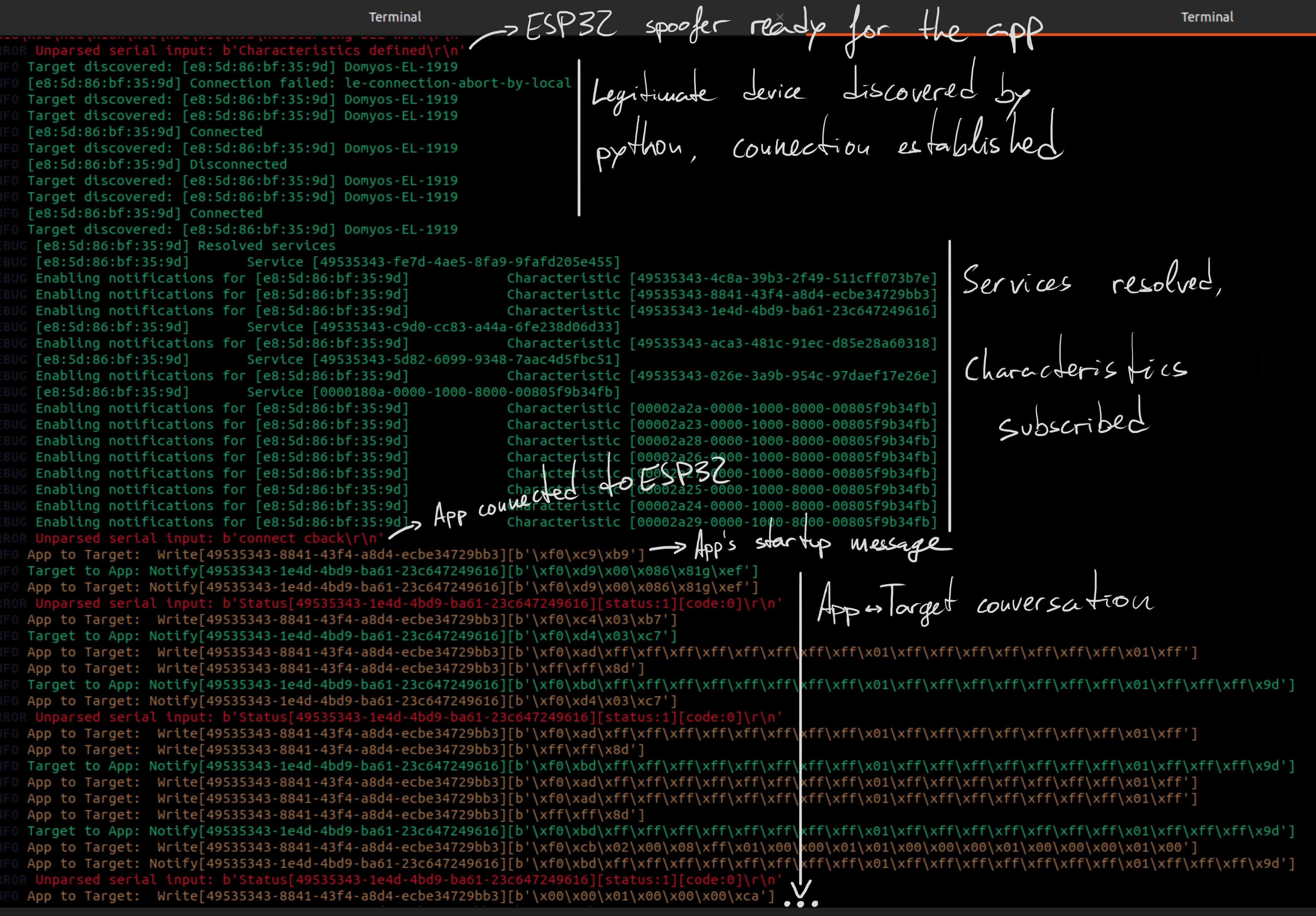

Python this, Arduino that, yadda yadda… Just a bunch of buggy spaghetti code to relay the relevant BLE messages over serial and give me pretty logs to read through.

Success! I have successfully put myself inbetween the app and the device, and am capable of intercepting and modifying the messages at will. Everything is logged in real time in a format of my choosing, which makes the packet analysis much easier.

This is enough insight to satisfy my current “needs”: Create a custom app that connects to the device and logs/displays its status over time.

To be continued…

At this point, rather than spending more time reverse engineering the protocol via raw packet analysis, I decided to take a step back and start writing the custom client. I’ll need it eventually anyway, and it’s gonna make packet forging and manipulation much easier, which in turn will make the protocol reversing quicker.

But I’m short on time lately, so that will have to wait for another day.

BTW, when working on projects like this, I often take handwritten notes as I go. This time I tried taking them digitally, so I figured I’d share them here. Yes, they’re rather unreadable… But they do the job, and I like them :) They’re the reason for all the crayon drawings in the post.

Anyway, I hope this post was useful to someone. Happy hacking!